Six hours in a southern Thai town to revisit a legendary backpacker’s footprints ended up with my own overnight journey on a Bangkok-bound ‘midnight express.’

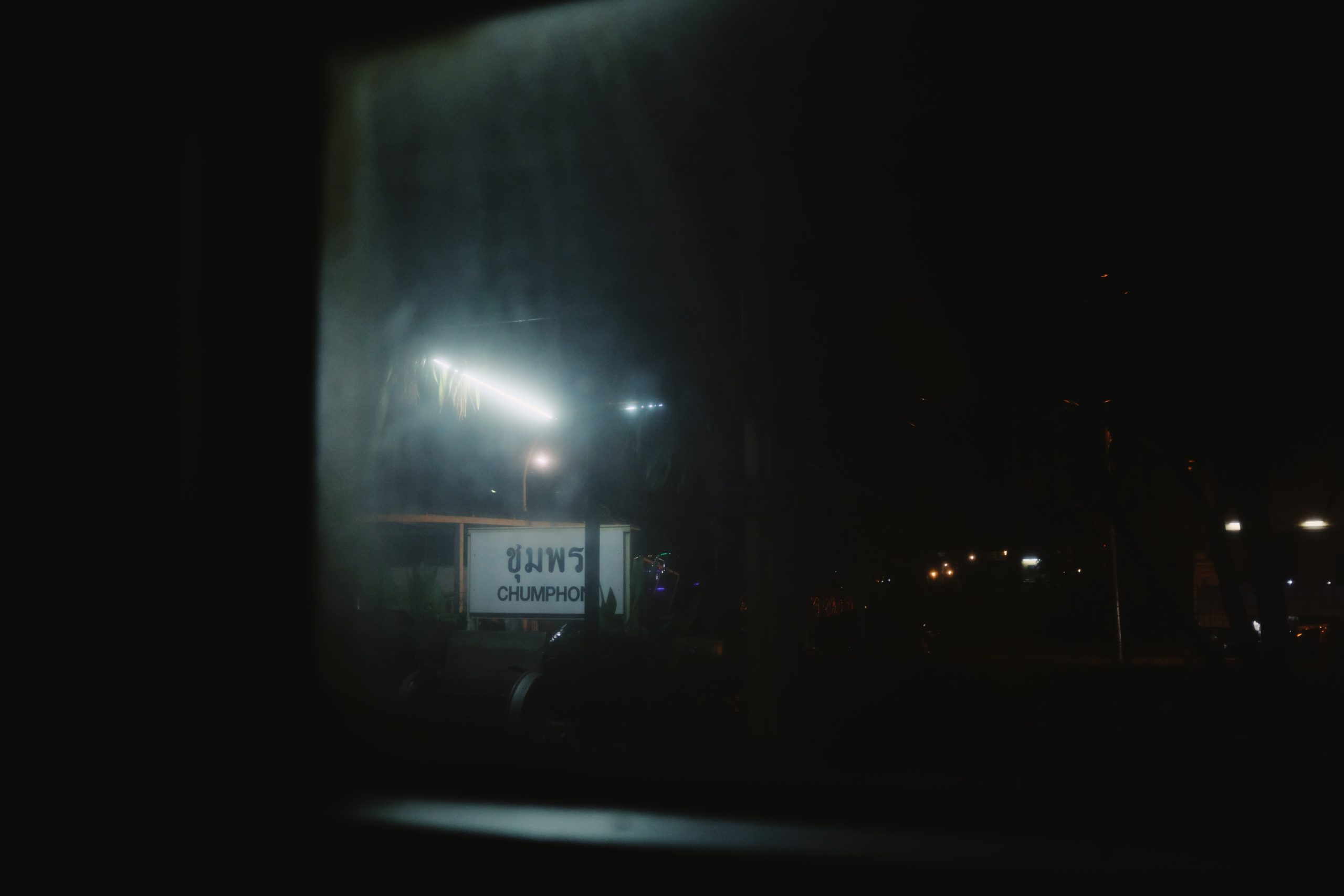

CHUMPHON. That wasn’t too an unfamiliar name when I was on a ferryboat cruising across the Gulf of Thailand. That day, the ferry departed an off-season resort island Phangan, headed for a provincial town in the mainland called Chumphon.

Chumphon.

The name had been lodged onto the back of my mind thanks to Midnight Express, a book by the Japanese nonfiction author Kotaro Sawaki.

The travel writing classic on his bus journey from Delhi to London in the early 1970s was one of my middle school bibles. A young adult jaded with the routine school life, I fancied the solo-backpacking throughout Eurasia again, and again.

Midnight Express starts with a long prologue for countries Sawaki explored before getting to Delhi — which actually comprised nearly half of the series. The chapters inspired my yearning for Hong Kong and Southeast Asia that still lasts today.

And Chumphon was a place Sawaki happened to stay for a night on his rail trip from Bangkok to Penang to Singapore. He spared a section for the excursion in the second volume of the paperback series. That passage was not an extensive but somewhat vivid one. The unique name of the town was, at least, memorable.

During my tranquil stay in the off-season island of Phangan, the tail of Sawaki’s brief stopover occurred to my mind when sketching out how to conclude the 10-day trip across Thailand.

Before Phangan, I had spent a few days each in Bangkok and the old northern city of Chaing Mai. And it was finally the time to head back to Bangkok to wrap up the vacation, retrieving my checked-in suitcase and catching a flight back home. Yet I’d do something interesting on the way back, instead of just leaping directly to the Don Mueang airport.

Realizing that a once-a-day ferryboat from Phangan would arrive on a coast in Chumphon Province in the evening, I decided to try the opposite way Sawaki ran through nearly a half-century ago: riding a northbound night train from the province.

The train I booked online was to depart Chumphon station at 11:23 pm. It sounded literally like a ‘midnight express’ experience in an homage to Sawaki’s essay.

I was quite excited about the plan when leaving a nearly empty hostel on the island, absent the partygoers who otherwise fill the bunk beds on certain on-season weekends.

The ferry released passengers, mostly holidaymakers including me visiting the gulf islands, at the pier around 4:30 pm. An hour of a connecting bus ride through marshy roads brought us to the town center.

It was at dusk. People in and out of the township were flocking to the downtown while stalls pop up on sidewalks. The main avenue began getting lit as the evening advances — motorbikes, cars and walkers started to stroll around the instant night bazaar. Yet unlike seen in Chiang Mai and some parts of Bangkok, the one in this town was far from being touristy.

A Night in Chumphon

“At a glance from the Chumphon station platform, I could find nothing but the tall, moonlit palm trees. No shops on the streets, much less an inn to stay over tonight, were in my eyesight.”

Kotaro Sawaki. Midnight Express (1986). Ch.5, § 2.

This is how Sawaki described the town on his 1973 visit.

Arriving at 3 am, he ended up at a budget hotel with the help of local youngsters acquainted on the night train from Bangkok. Indeed, the town should have appeared too rural for him after bogged down in the dusty, noisy capital city. He was there for weeks before eventually deciding to roll down the peninsula toward an international airport in Singapore.

Chumphon today isn’t that so stark. As a gateway to Southern Thailand, the eponymous province around the town has grown to have over 500,000 population. Businesses flourish, including a classy shopping complex where I charged my camera at its Starbucks shop inside.

Emblematic icons — young folks in sleek dresses or luxury cars — gave me a fresh sense of what the non-urban lives are like in the second-largest economy in Southeast Asia.

Traveling through the ASEAN region, swaths of mopeds crossing streets would not surprise you twice, but the difference in car presence across countries may give you a hint about how wealthy the place would be. In a ranking of the number of automobiles per capita, Thailand comes third in Southeast Asia after Brunei and Malaysia.

Even here in a local town not imbued with tourists or white-color office workers, I saw the rise of the Thai middle class obvious by looking at the traffic (and the underlying infrastructure).

Certainly, the upper peninsular part is not the least developed region in Thailand, which is more often associated with the southernmost provinces and the northeast Isan region. But the landscape here was sophisticated enough to defy my preconceived impression about the Thai countryside.

After strolling through the bustle of the main street, for being a little early for dinner, I pushed my way into the dimmer side of the downtown. Most back alleys had minimal amounts of streetlights which gave me a darker impression, together with the desolated stores and the bare light bulbs dangling on humble street shops that were still operating.

And one of such dark streets was where I saw a group of people sporadically standing or sitting on plastic chairs under the eaves. Some were chatting in front of a massage shop. Others were staring across the street. They were all women.

47 years ago in Chumphon, on the second floor at the guest house he woke up at 11 am, Kotaro Sawaki encountered an apparently forty-something woman when brushing his teeth. She was a prostitute having a little boy with her. Sawaki exhaustively described her appalling looks and tout for ‘sleep?’ while the boy was playing around them. The scene was snapped when the local youngsters from the previous night came to take him out for sightseeing.

The uncanny event made Sawaki feel ‘somehow dismal.’ He wrote it somehow made him leave the town right away, with a southbound train that departed Chumphone at noon.

This very abrupt episode might be what made the Chumphon section of the book unforgettable, though I kept no memory about the appearance of the woman itself until recently rereading.

In hindsight, the story in 1973 might be less relatable to what I witnessed on the Chumphon alleys today. I had no conversation with any of the women or I figured out nothing certain about them. Maybe there wasn’t anything shady about these standing women, or if any, sex works. I don’t think I should make any judgments.

But the atmosphere I subtly sensed there was, to be honest, murky. Murky enough to be reminded of fragments of knowledge on the darker side of tourism-heavy Thailand — human trafficking by organized crimes which could have been sustained by those sex tourists from wealthy nations, like from Europe, Australia and East Asia.

As a backpacker merely staying there for several minutes on my way, I could and did not dig any deeper. I wasn’t an investigative journalist. I only gave a thought to it. But when it comes to writing this essay, I might well mention my stream of consciousness among other stuff perceived in the town.

In addition to the physical pilgrimage, I am trying to follow Sawaki’s trail in nonfiction writing, too, at my best. I admire his candid and realistic (in the light of a 1980s male author) storytelling when he wrote about one of the big agendas in Midnight Express — inequality and sex industries across Asia.

Bustling Bazaar

It was already past 7 pm. I turned back to the main street in search of supper. Just approaching the edge of the night market zone, it now seemed at the height of the surges of crowds gathering around the stalls.

I kicked off with a snack. Deep-fried small doughnut called pa thong ko was my first bite. The woman at the snack stand put some fist-sized doughs into a bowl of oil and packed them into a paper bag while still hot.

Pa thong ko, said to be inspired by Chinese youtiao, had a taste as light as churros and much simpler than that. Hence it was served with a sugary, milky sweet dip sauce. Made with the herbal flavor of pandan leaves, the sauce was in green color but was less herby as I tried.

This little bite was quite good for my hungry stomach, yet with a bit cloying aftertaste. So I kept wandering to look for a simpler, and maybe a bit more spicy, main dish.

Amid the people up and down on the bustling street, I saw a couple of trans-women — not just once but twice. That encounter surprised me. I had heard of the diverse nature of gender identities in Thailand, albeit such tales always came with flamboyant images of night clubs and downtown Bangkok or Pattaya or Phuket.

Transsexuality seems no more a privilege of the liberal urban culture here unlike in other countries — at least on the level of a social landscape. I became curious about the origin of gender diversity in Thailand and its interplay with the social reform movements by the ‘enlightened monarchs’ (in the Western sense) of the modern Chakri dynasty.

Thanks to the municipality’s geography facing the coast, a variety of the Gulf seafood — shellfish, shrimps, minced fish, fish balls, etc. — were displayed at stands. Yet I was somehow hesitant about getting fresh food on the street, especially before the overnight train ride, concerning my digestion condition.

I thus went for a plate of khao man gai, a popular dish comprised of slices of poached chicken, steamed rice and cucumber garnishes.

It was such a reliable dish to me. Back in Japan, it was khao man gai that fixed my negative preference toward Thai foods largely because of prior experiences of too challenging menus, like a papaya salad. Its simple, pan-Asian taste (also widely known as Hainanese chicken rice) opened the door to the profound world of Thai foods for me. I should have appreciated it more.

So I ordered the classic for 40 baht or about US$1.30. “Can I have a dish of non-fried khao man gai?” was a phrase I got used to saying (though with a cheat sheet) in Thai through my 10-day trip. Receiving the plate and an accompanied plastic dish for the spicy sauce, I took the seat nearby with local aunties. Jut as expected, the plain chicken was fairly good, until I got too ambitious.

I don’t remember what exactly it was but that sauce with sliced raw chilis was pretty hot. Extreme spiciness was a feature of southern cuisine, I got to know later. My face turned wry with a bite after I poured the remainder of the chilis on the rice, and the aunty in front of me seemed puzzled. I looked for the word.

“Phet! Phet!” I appealed, pointing at the sauce cup. “Ah, phet,” she said. That was for ‘spicy.’

It was past 8 o’clock when I managed to finish the plate. As the fizz on the boulevard began waning, I made my way to the station.

Northbound Rapid No.170

In the book, Sawaki explained the origin of its title Midnight Express was taken from a euphemistic slang used by Turkish prisoners, to denote jailbreaking (which he got informed by a 1978 namesake Hollywood film).

An interesting fact about the book is that for the main part of his journey from Delhi to London, Sawaki imposed a stoic rule to use only local buses to move westward, to prove its viability to his friends. And indeed he obeyed it on his way through the Middle East and South Europe.

So despite what insinuated by the paperback series’ title and the cover-page image — A.M. Cassandre’s interwar French Art Deco poster of Le Nord-Express — the book had almost nothing to do with trains.

And this Malay Peninsula part was one of the few exceptions, granted that he could rely on any kind of transportation until up to Delhi. That was reasonable since, in 1973, no backpackers could readily travel on land from Hong Kong to Singapore to India. They should have avoided trespassing military-controlled Myanmar and newly independent, turbulent Bangladesh, not to mention the killing fields of the former Indochina.

I was not an ardent fan of railways, but as a member of the Japanese society or particularly as a Tokyoite, where one of the world’s most developed train networks thrive, a train had always been a thing when it comes to transportation.

But sleeping on a bed on an overnight train was — not at all. I knew there were still some sleeping trains operated in Japan, but the fares should be quite expensive, outstripped by cost-efficient flights and buses. Night trains were much less unfamiliar for passengers like me generally indifferent about how to move from point A to point B.

And now, I was about to undergo the first-time experience to lie on a bed that would carry me hundreds of miles away while dreaming. Not surprisingly, the name wasn’t that sexy — ‘Rapid Express No.170.’ But to me, it almost sounded like a magic carpet, with only a cost of 650 baht or around 20 bucks thanks to the State Railway authority.

Initially with that certain excitement, I reached the station more than three hours before the train’s planned arrival. It was because nowhere else seemed available to kill some time in the darkening downtown. The station front and platforms were filled with bright illumination and people waiting for later Hat Yai- (a southern city close to Malaysian border) or Bangkok-bound trains.

The bathroom near the end of the platform had a shower room you could use for a fee of a couple of baht. It was cold water-only in not so a clean facility, where somebody’s soap bars were littered on the floor, but I nevertheless appreciated it. It was after a long day spent on the ferryboat deck and probably before the next long day until getting to an airport shower room before a late flight.

And so finally, I came to a place where I had nothing else to do but wait. I even didn’t touch my phone or camera often for the fear of running out of battery if the train seat wouldn’t have a power socket (the intuition later turned out correct). I was just idly observing the surges of people after each train arrival.

Each arrival of night trains was like all of a sudden mix of din with a horn sound, PA announcements and chatters of those coming and going around the platform. Train passengers, police officers and peddlers with buckets filled with stuff like water or snacks for long-distance passengers, they all mingled around.

And ten minutes later or so, they were all gone after a whistle. That was one cycle and another round of lengthy waiting began. As the night wore on, fewer and fewer people popped up on the platform and accordingly, the station got quieter.

As perhaps expected, the train had not arrived at 11:23 pm ETA the timetable posted on the wall of the humble station building told me. The timetable by the way had multiple typos in English under Thai denotations, like ‘PAPID’ and ‘REPID’ (Wouldn’t it have been a mistake of a printing company the Chumphone station commissioned? As it should’ve been impossible to mistype rapid like those).

Soon, it turned out not that disastrous than I had worried. Around 11:45 pm, Rapid No.170 entered the platform with again, a loudspeaker voice the station staff made. Feeling a subtle sense of fatigue, I sought the second class coach I should be in. It was car 12, and my bed was the lower side of seat 12.

The first impression was — chill.

There were two types of second-class sleeping cars: one with only traditional electronic fans and the other with an air conditioning system, and mine was the latter. I actually knew an A/C car would be uncomfortably colder, but the fan car beds had been sold out when I booked it on the State Railway’s website. Reluctantly but out of necessity, I opened my backpack and took out as many outfits as possible to layer.

The power supply on the wall didn’t work as anticipated. So I turned off my camera and put my phone under the equipped pillow after setting up an alarm, while listening to a whistle. The train departed the Chumphon station. The glaring dial of my watch was showing it was around midnight.

Lying down the midnight express bed, that was like a peculiar feeling — sure, the floor swung and the sound of wheels incessantly grated on my ears to some extent. I soon worried I wouldn’t get comfortable all night. But the fatigue from the transportation and exploration earlier that day instantly led me to deep sleep. I didn’t wake up until the morning.

Later, last September, I had a chance to ride on a ‘sleeper bus’ from Phnom Penh to Siem Reap during my Cambodia trip with a friend. No less than a night train, the bus with bunk beds was shakier along the way. But I somehow dealt with it so easily, perhaps thanks to this prior experience of Rapid No.170.

Daybreak

It was around a quarter to 6 am when I woke up and stopped the alarm before it would ring. The window was facing east, displaying how a Thursday breaks out on the peninsular, though in a blurry picture. I groped for the glasses in my backpack and put them.

Soon the sun, amidst the fast-moving scud, came out and rose over the marshy ground.

Then I looked out of the window for a fairly long time, hearing the clickety-clack right beneath my bed. A myriad of palm trees, small rural depots, construction workers and lumber piles went by. Water streams indicated it might have been showery around here last night.

After a while, a train crew came to stow the bunk beds, lower of which are convertible to box seats. He was so adept at turning beds into seats in just 20 seconds or so each. Early-bird passengers came out of the green curtains to sit in the newly created booths, whereas some were still laying on the upper beds. The crew let them sleep quite a bit more.

It was now clear that Thursday was kicked off.

“Satani x…! Satani x…!” A loudspeaker repeated once arriving at another station along the way. That’s why I got the Thai word for ‘station’ for sure.

At larger stations where the train stops for several minutes, local salespeople briefly got onboard and walked down the aisle, yelling and peddling the breakfast. They sold a variety of foods. One merchant brought an electronic kettle for instant noodles or something. Another one came with a tray of jelly-like desserts.

On my way back from a bathroom, I visited the very tail of the train. There was a small window through which I could see the railroad tracks spanning straight up to the horizon on the plain. Crossing signs, maintenance crews, ponds and woods along the rails passed one after another.

A couple of morning hours went by accordingly. I began taking another nap once back to my seat.

Back to Bangkok

When I got up again, the urban skyline on the edge of the landscape frame suggested that we were about to approach the metropolis. The outskirts along the railroad turned to be slums for impoverished people. They were living in tin-roofed houses surrounded by sewerage and piles of plastic garbage.

At around 10 am, Rapid No.170 eased into the Bangkok central terminal with an hour delay. “Satani Krung Thep,” a station attendant announced referring to the common Thai name of the city.

Getting off to the hustle-and-bustle station, I dropped by a public canteen. I ordered a plate of economy rice with beef barbeque and cabbage for a late breakfast. After breakfast, I turned my way to the subway entrance to get to a deposit warehouse in Khlong Toei district, where I checked in my suitcase.

That would mark the end of my trip to South Thai and a humble pilgrimage to Kotaro Sawaki’s tracks.

Note: my visit to Thailand actually happened in May 2019. I wrote this photo-essay as a throwback after a year with reminiscences — pictures and memories — amid the almost everlasting quarantine life without any clue of traveling.

Still incredible is the process Sawaki crafted Midnight Express; he published its first volume a decade after his journey in the early 1970s, and the final one was out in 1992.